ABSTRACT

In developing countries like India, there are large urban slums with a high proportion of people who don’t have a proper formal education. This study explores how primary education can help raise income levels and make a big difference to the lives of slum dwellers.

This is also a case study of some leading schools in Dharavi - Asia's biggest slum spread across 2.1 squarekilometers with a population of about 1 million, located in Mumbai – and their teaching standards. We also look at factors due to which slum-children drop out of primary classes and what can be done to reduce the drop-out rate and promote education.

This research project focuses primarily on primary education which can be the lifeline to urban slum transformation in Dharavi.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last two decades, India has witnessed rapid economic development in both its industrial and service sectors, leading to an increase in urbanization. Owing to a high official unemployment rate of 6.5% (as per CMIE, November 2020) – with many of the unemployed not even properly recognized in such official statistics - migrants are increasingly moving to urban cities in search of jobs, and new pockets of "urban slums" are emerging due to the lack of affordable housing.

In a city where house rents are among the world's highest, Dharavi provides a cheap and affordable option to those who move to Mumbai to earn a living (sometimes as low as Rs.185/US$2.5 per month). Despite its residents’ low-income status, Dharaviis home to a large number of thriving small-scale industries producing embroidered garments, export quality leather goods, pottery, and plastic. The level of economic achievement is closely linked to educational achievement, family planning, and parenthood which facilitates the development of the next generation for achievement at levels higher than those of their parents and grandparents. In fact, Dharavi is said to be one the most literate slums in India with a literacy rate of 69%.

At the time of India's independence, the national gross school enrolment rate for children in the 6-14 age groups was just 42.6%. The rate reached high as 96.3 %. But on the other side, the reality is that 42% of such children enrolled still drop out of school before completing primary education and another 19% drop out at the Class VI-VIII level (Census 2001). This wastage of financial outlay on children, who were in the school system but subsequently dropped out and lapsed into illiteracy, runs into several million rupees. Education allows children to break the cycle of a life of poverty, arising from illiteracy, freeing themselves from the low-income salaries of minimum wage workers.

However, at Dharavi, many children are unable to complete their school education and hence unable to break out of the poverty lifecycle. In this research, we review some of the barriers to education, which include low-income levels of parents, socially constructed gender roles prohibiting girls from their right to education, lack of quality resources, child labour, staying home to look over younger siblings while parents are at work, etc.

Finally, in this research paper, after going through the various factors impeding primary education of children in Dharavi, we list some specific practically implementable suggestions that can help reduce the drop-out rate of such children, improve the overall quality of education, and help such slum-children to breakout of the poverty cycle.

SCOPE

A case study for the selected schools located in Dharavi slums and its impact on overall transformation of Dharavi slums in Mumbai. This research project focuses only on primary education (not secondary education).

METHODOLOGY

In order to conduct an in-depth case study of selected schools in the urban slum of Dharavi, and its educational impact on the overall transformation of the Dharavi slum, secondary data analysis was used in order to draw pertinent conclusions. The data about schools’ infrastructure and enrolments has been collected with the help of www.indiastat.com. Through interviews with principals, teachers of selected schools, parents of primary school children, NGOs and the concerned authorities, primary data was collected to help research the importance and impact of education on the development of the slum of Dharavi. Further, a literature review was conducted to understand the existing infrastructure problems and enrolment pattern in schools.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS

Education as a key requirement for development:

Starting off with context regarding how students’ growth runs parallel to that of the nation, and is reflected through the learning and experience imbibed and stimulated over the years, this section covers how education provided at a young age helps in reducing global poverty, improving health, fostering peace, bolstering democracy, improving environmental sustainability and increasing gender equality.

Barriers to education:

With multiple layers to its complexity, each barrier helps us further analyze and understand the constraints of the educational system fit into a child’s economic, social, and familial scenario. This section covers how poverty, illiteracy and poorly educated parents, socially constructed gender-roles, lack of easy access to primary school near residence, health & hygiene factors, safety, unpaid or unmotivated teachers, lack of toilets in school, disease outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics together act as barriers to education.

Importance of primary education:

In a more focused sense, this section covers how primary education helps develop basic skills and abilities, can help fight income and gender inequality, can help reduce stunting, violence at home, and vulnerability to infections and diseases, can help reduce unemployment and create professional manpower leading to an improved standard of higher education and living.

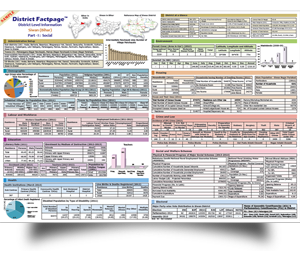

Case study of schools in Dharavi:

With authentic data collected from report cards of 33 schools, this section takes into consideration a variety of school parameters and facilities. From a physical infrastructure perspective, the data shows that primary schools in Dharavi are in reasonably good shape. All the primary schools in Dharavi have separate toilets for boys and girls, classrooms in good condition, drinking water, electricity, and internet connection.

Areas of improvement for policy-makers:

Students are no longer looking at school facilities, but those school factors that enable and provide progressive opportunities for employability. This education includes digital learning through laptops, tablets, and desktops and encourages students to study in schools with English as the medium of instruction – this is where policy-makers should redirect resources and efforts.

Survey of parents and teachers from Dharavi:

The main positive is thatearlier, a major problem faced by teachers was the lack of discipline by students: whether it was in the form of hygiene or focus in studies. Students are slowly changing, becoming more independent which scales up to a greater standard of living. The negatives boil down to low incomes resulting in an inability to pay fees on time, hectic parent schedules due to changing employment opportunities, lack of access to educational resources etc. Surveys regarding the COVID-19 impact on primary education in Dharavi highlighted the difficulty in attending online classes due to the shortage of devices and internet, as well as low attendance resulting in a fall in the quality of education.

CONCLUSION

A better primary education infrastructure and inclusive enrolment in Dharavi slums could cause the transformation of overall urban environment of Mumbai and will explore the new opportunities for higher education enrolment and professional, skilled manpower.

PART 1 – WHY PRIMARY EDUCATION IN URBAN SLUMS IS IMPORTANT

1.1 Education: A Key Requirement for Development

Most economists would probably agree that it is the human resources of a nation, that ultimately determine the character and pace of its economic and social development, not its capital or its natural resources.

India has a very low literacy rate, of about merely 72.98%, in spite of a young population for the year 2011. The female literacy rate stands at a shocking 64.63%, even 73 years after independence. The emphasis placed on education as a central piece of world growth, progress, and development - “education for economic success” does not have an unfamiliar ring to it. In order to truly tap and reap the benefits of the extent of human potential, it is essential that everyone has access to education. It is not just education, but its relevance to development that brings the larger picture into perspective.

According to UNICEF, getting every child in school and learning is crucialin order to reduce global poverty, improve health, foster peace, bolster democracy, improve environmental sustainability and increase gender equality. This is very relevant for India in particular which has a large number of people below the poverty line –the number of poor in India was estimated at 364million (United Nations, 2019), and with the Covid pandemic, this number would have certainly increased.

However, to harness all the potential of this human resource, primary education holds utmost importance due the impressionable minds of students at this age.

The foundational skills acquired by children in their early years make a lifetime of learning possible, due to the early exposure and encouragement both inside and outside of the formal schooling system. This education not just stimulates, but also integrates core values and skills: social, cognitive, cultural, emotional and physical. Primary education can help raise self-esteem, build social skills, and produce well-rounded individuals. Such students in turn can enlighten their families about the world, preventive health, legal rights, the negative effects of school dropout and early marriage – which are typically seen in poor families. It is primary education that prepares young children for life and the workforce, and helps reduce extremism, encourage political participation and promote intercultural learning and respect.

During the years of secondary education, a majority of students in India drop out to earn money to support their families, or merely the heavy burden of the cost of education, which doesn’t make it very effective. Hence, the focus on primary education is of utmost importance to begin with. If children do not get a primary education, then the scenario of trying to get them to continue studying will not even materialize.

These students represent the youth of India, where their growth runs parallel to that of the nation, and is reflected through the learning and experience imbibed and stimulated over the years. Society’s thread of the growth depends majorly on the quality of education that is being imparted, and the extent of its reach. A quality education has several dimensions: it understands the past, is relevant to the present and has a view to the future.

Furthermore, it is primary education in India’s urban slums that should be of particular importance to policymakers. As villagers continue to migrate to large urban centres in search of employment – it is worth noting that about 50% of India’s population depends on agriculture which accounts for only 15% of GDP (Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, 2019) – they typically end up living in slums given their meagre incomes and lack of low-cost housing in most cities.

Such urban slums have been increasing in size and population over the years, and as the rural-to-urban migration accelerates in the coming years, the number of children in urban slums not getting even a primary education will keep increasing unless urgent action is not taken.

1.2 Why we are focusing on Dharavi

Urban slums in India are typically poorly built congested tenements, in an unhygienic environment, lacking inadequate infrastructure, proper sanitary or drinking water facilities. India’s urban slums are experiencing a population explosion: the census for 2011 estimates that about 65 million Indians live in urban slums.

Dharavi is the biggest slum in India, located in Mumbai, with an estimated population of about1mn (exact population unknown). It has all the characteristics of a typical, large urban slum:

With a literacy rate of 69%, Dharavi is also the most literate slum in India – although in absolute terms this is still low. Hence, it is a good example to study on how primary education is carried out in such a large urban slum and what are the main lessons for policymakers.

Background:

The slum of Dharavi was founded in 1884 during the British colonial era and it grew in part because of an expulsion of factories and residents from peninsular city center by colonial government and from rural poor migrating into urban Mumbai, then called Bombay. At India's independence from colonial rule in 1947, Dharavi had grown to be the largest slum in all of India and it still had a few empty spaces.These continued to serve as waste-dumping grounds for operators across the city. Mumbai, also growing in the meanwhile, soon surrounded Dharavi by the city and became a key hub for informal economy.

Dharavi is now a sprawling slum in the heart of Mumbai, India’s financial and entertainment capital, and has an area of just over 2.1 sq. km. (0.81 mi2; 520 acres).

With a population of about a million living in approx. 55,000 dwelling units, and a population density of 3.4 lakh per km2 (Ramasamy & Sundararajan, 2020), Dharavi is one of the most densely populated areas in the world.Dharavi comprises of nearly 15,000 single-room factories and 5000 businesses (Alam&Matasuyuki, 2020). Worldwide, Dharavi is recognized as one of the most densely populated urban agglomerations. Other than an ever-increasing population density, the dearth of hygiene and awareness, miniature homes and low income has exacerbated living conditions in Dharavi.

Dharavi’s slum residents are from all over India, most of which are people who migrated from the rural regions of many different states. About 30% of the population of Dharavi is Muslim, compared to 14% average population of Muslims in India. The Christian population is estimated to be about 6%,while the rest are predominantly Hindus (63%), with some Buddhists and other minority religions (Census, 2001). Due to this, Dharavi is considered a highly diverse settlement, both religiously and ethnically.

Dharavi has an active informal economy in which multiple household enterprises employ many of the slum’s residents—leather, textiles, and pottery products are among the goods made inside Dharavi. The total annual turnover has been estimated at over US$1bn.

Dharavi has severe problems with public health. Water access derives from public standpipes stationed throughout the slum. Additionally, with the limited lavatories in the slum, they are extremely filthy and broken down to the point of being unsafe. Mahim Creek is a local river that is widely used by local residents for urination and defecation causing the spread of contagious diseases.The open sewers in the city drain to the creek causing a spike in water pollutants, septic conditions, and foul odors. Due to the air pollutants, diseases such as lung cancer, tuberculosis, and asthma are common. There are several government proposals in play with regards to improving Dharavi's sanitation issues. Residents have a section to wash their clothes in water that people defecate in, a major cause for concern. This causes a huge spike in hygiene-based diseases; doctors have to deal with over 4,000 cases of typhoid a day.

Overall, Dharavi’s residents are examples of the urban poor living in numerous Indian cities and their day-to-day lives are beset with all kinds of socio-economic problems. In this context, it is interesting to see whether primary education can make a difference to the lives of Dharavi’s residents, and what can be done to improve such education and reduce school drop-out rates.

1.3 Barriers to Education

Education has been recognized as a fundamental right ever since the United Nations General Assembly adopted Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in December, 1948: “Not only does everyone have the right to a free and compulsory primary education, that education should focus on full human development, strengthen respect for human rights, and promote understanding, tolerance and friendship (UDHR Article 26).”

Governments allocate a significant portion of their annual expenditure budget towards providing the youth of our nation with education. However, in spite of such efforts, there still stand barriers that hinder a child’s access to and completion of their education. With multiple layers to its complexity, each barrier helps us further analyze and understand the constraints of the educational system fit into a child’s economic, social, and familial scenario. The lack of access, in most cases, is a combined result of the limitations provided by multiple barriers, and not just an isolated single one for each student.

The following are some of the main reasons for children not getting a good primary education in most urban slums:

Poverty: This includes direct and indirect costs. The direct cost includes the out-of-pocket expenses borne by the family such as school fees, textbooks, uniforms, transportation, and food costs. The indirect costs include the value of the child’s time and effort, measured in terms of the income forgone. If not in school, the child would be working at a job to provide income and support the family. In some cases, where parents have debts to be paid off, children are enslaved and sent off to work below the legal working age. This hampers the child’s physical and mental potential and development, and deprives children of their childhood.

Illiteracy and poorly educated parents: Most slum dwellers are poorly educated, with many of them illiterate. While our survey (see next section) shows that most slum-dwellers recognize the importance of education for their children and are willing to work hard for it, there are still some parents who would rather have their children focus on earning money for the family and do not consider primary education to be very important.

Socially constructed gender-roles: In a traditional country like India, where gender discrimination is still prevalent, gender can be a key determinant of who does what, who has what, who decides, who has power, and even who gets an education or not. In many societies, boys are seen as the ones who should be educated, while girls are expected to remain confined at home. Intractable patriarchal societies often result in lower priority given to girls’ education: they are told to remain home, cook, and look after younger siblings in the absence of parents, and are even married off early at ages as early as 11 or 12. According to the UN, one-third of girls in the developing world wed before the age of 18, and one in nine get married before the age of 15. In most cases, marriage and childbearing implies the end of a girl’s formal education. Overcoming these gender inequalities requires profound transformations in social structures and relationships between men and women. This gender inequality becomes apparent in unequal access to education.

Lack of easy access to primary school near residence: While Dharavi does have several primary schools within its slum area, many slums don’t have such easy access to a school. Additionally, certain forms of human migration create barriers to school access as each one involves the migration of children, sometimes but not always with their families, far from their home communities. Sometimes, schools are situated in relatively geographically inaccessible areas. Mountainous areas, steep hillsides, river basins are a few of such physical barriers, although none of these are barriers for Dharavi schools.

Health & hygiene factors: The high population density in urban slums such as Dharavi leads to unsanitary conditions (e.g. an inadequate number of toilets, insufficient water supply) further causing health and hygiene issues which causes students to fall sick and not attend classes.

Safety: Given alcoholism, drug abuse and gang violence which is often seen in urban slums, school administrations find it difficult to operate in slum areas. It is not just the teachers who feel unsafe, but also the children who may be fearful of walking to school. Sometimes a parent maybe an alcoholic or resorting to domestic violence, which makes it even more difficult for children of slumdwellers to attend school regularly.

Unpaid or unmotivated teachers: In developing countries, fiscal deficits are the norm and the government machinery is often inefficient in making payments for various educational programs and subsidies. As a result, sometimesteachers don’t get paid on time or don’t get paid for months at a time. Many have no choice – they either must quit their posts to find others sources of income or are moved to other districts. Schools struggle to find qualified teachers to replace those who have left, ultimately leading to a decline in the quality of teaching. Without qualified teachers in the classrooms, children suffer.

Lack of toilets in school: Although this is not a problem in Dharavi’s schools, many primary schools in urban slums have no toilets (let alone separate bathrooms for boys and girls). This impliesmissed school days for kids with minor stomach bugs — or for girls who get their period. It is estimated that girls around the world miss up to 20% of their school days due to their period, as per the World Bank. Usually this is because they don’t have sanitary pads or private bathroom facilities. Widespread availability and access to clean and safe toilets can potentially increase the amount of time that children spend in school.

Disease outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics: Even if the students are healthy, they may be kept out of school if an epidemic has hit their area. Teachers might get sick, and families with sick parents may require children to stay home. Quarantines can go into effect.This has been most vividly illustrated in the ongoing Covid pandemic due to which primary schools in urban slums like Dharavi have been most badly impacted – local authorities have disallowed in-person classes in schools and such primary school students and teachers do not have the resources to engage in online education (due to lack of money to buy smart phones, tablets, etc).

1.4 Why is Primary Education so important?

According to UNESCO, if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills (nothing else), an estimated 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. If all adults completed secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

In this context, it is worth noting that India has a very low literacy rate, of merely 72.98% for the year 2011, despite having a largely young population.

Education serves as a crucial component for the socioeconomic development of the individual, community, and the country. The emphasis on education as a central piece of growth (at both the individual and societal scale) - “education for development” is not an unfamiliar concept. In order to truly tap and reap the benefits of human resources and their potential, it is essential that everyone has the correct access to education. It is not just education, but its relevance to development that brings the larger picture into perspective.

Primary education holds utmost importance due the impressionable minds of students at that age. The foundational skills acquired early in childhood make a lifetime of learning possible, due to the early exposure and encouragement both inside and outside of the formal schooling system, according to the science of brain development. This education stimulates and integrates core values and skills: social, cognitive, cultural, emotional, and physical, which are much needed in the future.

These students represent the youth of India, where their growth runs parallel to that of the nation and is reflected through the learning and experience imbibed and stimulated over the years.

Society’s thread of growth depends upon the quality of education that is being imparted, and the extent of its reach.

Primary education helps provide the basic reading skills, but it is not just reading that is important to change students’ lives. Here are three ways that education affects poverty.

1.5 Introduction for a case study of schools in Dharavi

Given Dharavi’s estimated population of about 1mn, a detailed search and analysis shows that most primary schools are unregistered and self-funded or privately funded.

It isn’t easy to get accurate data on all the small, unregistered schools with small class sizes.Since much primary data collection was not possible, we collected data for each school from the government website. Information for each school (regarding students, teachers, facilities available, school background, etc.) is collected and uploaded regularly by the government in the form of a school report card. This is authentic data in a standardized format and can be used for analysis every two years when data is collected.

Our data collection had the following parameters: school district, school type, classes taught, medium of instruction, building status, availability of ramps and handrails, mid-day meals, availability of roads, number of toilets for girls and boys, library, drinking water availability, playground, furniture, electricity, medical checkup facility, internet, ICT lab, desktops, printers, projectors, laptops, free textbooks, number of male and female teachers, number of girls and boys, and total strength.

The given table contained data for 33 schools located in the Dharavi area with a total enrollment of 12114 students. Of these, 29 schools offer primary education (defined as having classes 1-8) with 10296 students for the year 2018-19.

However, only 14 out of the 29 schools offering a primary education are run by the Mumbai Municipal Corporation. The rest are privately funded or self-financed schools.

| Name of Schools | Managements | School Category | No. of Students | Lowest & Highest Class | Medium of Instruction |

| Dharavi Mun URD 1 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary | 464 | 1-4 | Urdu |

| Dharavi Cross Road Lp Urdu School No.2 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary | 209 | 1-4 | Urdu |

| Dharavi Mun Up Mar | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 16 | 1-7 | Marathi |

| Raje Shivaji Vidhyalaya URD | Private Unaided | Primary | 270 | 1-4 | Urdu |

| Raje Shivaji Vidyalaya Dharavi English | Unrecognized | Primary | 263 | 1-4 | English |

| Raje Shivaji Vidyalaya Dharavi Hindi | Private Unaided | Primary | 131 | 1-4 | Hindi |

| Raje Shivaji Vidyalaya Dharavi Marathi | Private Unaided | Primary | 88 | 1-4 | Marathi |

| Shed Primary English School | Unrecognized | Primary with Upper Primary | 327 | 1-7 | English |

| Morning Star English School | Private Unaided | Primary | 426 | 1-4 | English |

| People's Education Society's Maharashtra High School English; | Self Finance School | Primary | 287 | 1-4 | English |

| Dharavi T.C. Mun English Secondary School | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Secondary Only | 264 | 9-10 | English |

| Dharavi Kalakilla Mun Marathi Sec. School | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Secondary Only | 64 | 9-10 | Marathi |

| Dharavi T C Mun Sec. Marathi School | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Secondary Only | 31 | 9-10 | Marathi |

| Jamia Umar School | Unrecognized | Primary | 82 | 1-5 | English |

| Dharavi T C Mun Mar | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 186 | 1-8 | Marathi |

| Dharavi T C Mun Up Eng No.1 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 1425 | 1-8 | English |

| Dharavi Tc Mun Urdu No 1 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 629 | 1-8 | Urdu |

| Shramik Vidyapith Voc Mun URD | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 585 | 1-7 | Urdu |

| Dharavi T C Mun Up Tml | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 85 | 1-7 | Tamil |

| Maulana Azad Primary | Self Finance School | Primary | 318 | 1-4 | English |

| North Indian Education Soc | Private Unaided | Primary with Upper Primary | 525 | 1-7 | English |

| Dharavi T C Mun Eng No.-2 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 657 | 1-7 | English |

| Dharavi T C Sec URD | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Secondary Only | 330 | 9-10 | Urdu |

| Shramik Vidyapith Mun. URD Sch No.2 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 818 | 1-7 | Urdu |

| Dharavi T C Mun Up URD No.2 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 600 | 1-8 | Urdu |

| Dharavi Kalakilla Mun Mar No.1 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 506 | 1-8 | Marathi |

| Dharavi Kalakilla Mun Up 2 | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Primary with Upper Primary | 229 | 1-7 | Marathi |

| Mumbai Public Eng Sch | Municipal Corporations (MNC) | Pr. Up Pr. and Secondary Only | 1127 |

1-10 |

English |

| Mother Theresa School | Unrecognized | Primary | 349 |

1-4 |

English |

| Royal City of English School | Unrecognized | Primary | 225 |

1-4 |

English |

| Al-Marif English School | Self Finance School | Primary with Upper Primary | 321 |

1-7 |

English |

| Al Qalam English School | Unrecognized | Primary with Upper Primary | 201 |

1-7 |

English |

| Farhan Edu.Soc. Gausiya English Sch | Unrecognized | Primary with Upper Primary | 76 |

1-5 |

English |

| Janata Shikshan Sanstha Sunrise English School | Private Aided | Primary | - | - | - |

| Grand Total | 12114 |

When we analyze the 29 schools offering primary education, we find that 12 schools offer only a lower primary education (Std 1-4), 16 schools offer lower and upper primary education (standard 1-8) and only 1 school offers an education all the way from lower primary to secondary (standard 1-10).

In terms of the medium of instruction, only 15 out of 29 primary schools have English as the medium of instruction with a net enrolment of 6609 students (57.8% of total).

| School Category | English | Urdu | Marathi | Hindi | Tamil | Total | |

| Lower Primary | Std 1 | 1000 | 503 | 121 | 35 | 11 | 1670 |

| Std 2 | 908 | 551 | 159 | 30 | 10 | 1658 | |

| Std 3 | 943 | 573 | 149 | 33 | 15 | 1713 | |

| Std 4 | 940 | 532 | 141 | 33 | 17 | 1663 | |

| Upper Primary | Std 5 | 532 | 410 | 120 | 0 | 12 | 1074 |

| Std 6 | 503 | 360 | 82 | 0 | 11 | 956 | |

| Std 7 | 489 | 396 | 72 | 0 | 9 | 966 | |

| Std 8 | 301 | 250 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 596 | |

| Total | 5616 | 3575 | 889 | 131 | 85 | 10296 | |

| % of total | 55% | 35% | 9% | 1% | 1% | 100% |

The other interesting aspect an analysis of the Dharavi schools’ data show is that the enrollment of girls is reasonably close to that of boys in the lower primary classes (48% vs 52%), but the proportion starts deteriorating in the upper primary classes (46% vs 54%).

| School Category | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | |

| Lower Primary | Std 1 | 865 | 805 | 1670 | 52% | 48% |

| Std 2 | 860 | 798 | 1658 | 52% | 48% | |

| Std 3 | 869 | 844 | 1713 | 51% | 49% | |

| Std 4 | 859 | 804 | 1663 | 52% | 48% | |

| Upper Primary | Std 5 | 578 | 496 | 1074 | 54% | 46% |

| Std 6 | 522 | 434 | 956 | 55% | 45% | |

| Std 7 | 531 | 435 | 971 | 55% | 45% | |

| Std 8 | 312 | 284 | 564 | 52% | 48% | |

| Total | 5396 | 4900 | 10296 | 52% | 48% |

From a physical infrastructure perspective, the data shows that primary schools in Dharavi are in reasonably good shape. All the 29 primary schools in Dharavi have the following:

Most primary schools have a library, a playground and offered a medical checkup. However, 15 and 17 of the 29 primary schools did not offer free textbooks or uniforms respectively.

| School Category | No. of schools | ||||

| Free Text Books | Free Uniforms | Library | Playground | Medical Checkups | |

| Lower Primary Only | 2 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Lower Primary with Upper Primary | 11 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

| Primary, Upper Primary and Secondary | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 14 | 12 | 23 | 22 | 23 |

Furthermore, the data suggests that the average class size in Dharavi is reasonable at 36 students per classroom. A smaller class size would be better, but given the low-income levels of parents of students in such schools, this is reasonable in the current economic environment.

| School Category | # of students | # of classrooms | students/classroom |

| Lower Primary Only | 2794 | 78 | 36 |

| Lower Primary with Upper Primary | 6643 | 188 | 35 |

| Lower Primary, Upper Primary and Secondary | 1026 | 27 | 38 |

| Total | 10463 | 293 | 36 |

Across the world, one of the most important determinants of success of primary education is the proportion of female teachers. In Dharavi, the figure is a reasonably high 70%, and at the lower primary level it is even higher at 88%.

| School Category | Teachers | ||||

| Male | Female | Total | % Male | % Female | |

| Primary Only | 10 | 70 | 80 | 13% | 88% |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 80 | 140 | 220 | 36% | 64% |

| Total | 90 | 210 | 300 | 30% | 70% |

One issue which is often found in some urban slums is that primary school teachers are not full time employees and they are either part-time workers or on contract. Thankfully, in Dharavi, 99% of the primary school teachers are regular employees.

| School Category | Regular | Part-time | Contract | Total |

| Primary Only | 78 | 0 | 2 | 80 |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 220 | 0 | 0 | 220 |

| Total | 298 | 0 | 2 | 300 |

| % of total | 99% | 0% | 1% | 100% |

A majority of teachers in Dharavi’s primary schools have not completed graduation. Graduates or post-graduates account for only 38% of total teachers in the schools.

| School Category | Below-Graduate | Graduate | Post-Graduate | Total |

| Primary Only | 69 | 11 | 0 | 80 |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 118 | 79 | 23 | 220 |

| Total | 187 | 90 | 23 | 300 |

| % of total | 62% | 30% | 8% | 100% |

However, 73% of teachers in Dharavi’s primary schools have a diploma or certificate in teaching, and another 21% have a Bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education or in Education.

| School Category | Diploma/Certificate | B. Elementary Education | B.ED | Others |

| Primary Only | 70 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 149 | 17 | 38 | 16 |

| Total | 219 | 17 | 45 | 19 |

| % of total | 73% | 6% | 15% | 6% |

When it comes to computer skills, 59% of Dharavi’s primary schools have had computer training and 41% do not have any computer training.

| School Category | Without Computer Training | With Computer Training | Total |

| Primary Only | 41 | 39 | 80 |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 135 | 85 | 220 |

| Total | 176 | 124 | 300 |

| % of total | 59% | 41% | 100% |

Similarly, Dharavi’s primary schools do not have extensive technology infrastructure – whether it’s an ICT Lab or internet access, However, penetration of tablets is satisfactory.

| School Category | ICT Lab | Tablets | Internet | Total |

| Primary Only | 0 | 7 | 12 | 19 |

| Primary w/Upper Primary | 3 | 329 | 15 | 347 |

| Total | 3 | 336 | 27 | 336 |

| % of total | 1% | 92% | 7% | 100% |

1.6 Areas of improvement that policy makers should target

1. Free Textbooks

As the number of free textbooks provided in school increases, the number of students (total strength) increases too. The provision of free textbooks reduces the burden of the cost of education on the parents by a large amount. Students can have access to necessary course materials required for classes, providing them with better chances of success. Without these free textbooks, students may have to pay for them, making them take up part-time jobs at a young age, or they may not buy textbooks at all. This leads to a lack of understanding, and hence, interest in studies which further causes them to drop out of school.

2. Female Teachers

The general trend is that as number of female teachers increases, the total strength also increases. Evidence suggests that female teachers are likely to increase the likelihood that girls remain in school and ease any safety concerns that students or parents may have.

Additionally, it is very important to expose students (especially girls) to look up to accomplished female role models as much as possible. Women, as teachers, can raise gender awareness and the sensitivity of male teachers, while also helping to promote important behavioral patterns in students. Female empowerment in the education sector can create a school environment that can makes girls feel comfortable to learn and grow.

3. Desktops

Trends show that for more desktops provided in a school, there tend to be more students (with a few exceptions). Digital learning has become a very usual occurrence in the modern world and is even replacing most traditional educational procedures. It has not only made learning mobile, but also interactive and engaging, which motivates students to maintain interest.

Furthermore, digital learning tools, and technology sharpen critical thinking skills which are the basis for the growth of systematic reasoning. Nearly every employment opportunity nowadays involves some degree of technological proficiency. Providing and teaching students how to use desktops, tablets, and phones has made education available to all by addressing the constraints of traditional models of learning.

4. Medium of Instruction

This parameter can be overlooked easily, but we see an interesting observation. Schools with an English medium of instruction see a higher number of students, despite being in the state of Maharashtra, where the language spoken is Marathi, and despite the large Muslim population in Dharavi, which typically speaks Urdu.

This shows that students are now showing a preference for primary and mainstream languages such as English, which can help them with a wider variety of employment opportunities in the future and does not restrict them to a relatively uncommon language such as Urdu or Telugu or Kannada.

5. Toilets

Toilets are considered an important factor when it comes to school facilities. Previous research shows that a large number, nearly 23% of girls, drop out of schools in India because of the lack of sanitation facilities when they reach puberty, due to menstruation.

However, the uniform distribution of our data shows us that toilets are not a very important factor when it comes to girls’ education in Mumbai’s Municipal Schools. This is possibly because in the short schooling hours, students do not feel the need to utilize the toilet facilities.

Additionally, a lot of funds have been directed towards sanitation programs in such schools, which is why most schools have an adequate number of health and hygiene facilities with respect to the number of students. This does not bring out a need for focus on sanitation facilities in toilets in these schools.

6. Mid-day Meals

Previously, during field surveys it was learned that in some schools, children come to school only to have the lunch provided by the school since most of them belong to socially and economically weaker sections of the society. However, our surveys and interviews suggest otherwise. Schools providing and not providing meals have approximately the same number of students. This is possibly because the government has a lot of schemes in place to provide the families with food grains, and the students no longer feel the need to drop out of school on the basis of whether meals are provided or not.

The table below summarizes a few of the government schemes that provide aid to municipal schools.

| Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan | Mid-day Meal Scheme | Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan | Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan |

| Aim: to open new schools in those habitations which do not have schooling facilities and strengthen existing school infrastructure through provision of additional class rooms, toilets, drinking water, maintenance grant and school improvement grants | Aim: provide cooked mid-day meals with 300 calories and 8-12 grams of protein to all children studying in Government and aided schools and EGS/ AIE centres, with a view to enhance enrolment, retention and attendance and while simultaneously improving nutritional levels among children | Aim: to ensure that every school in India has a set of functioning and well maintained water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities (a combination of technical and human development components that are necessary to produce a healthy school environment and to develop or support appropriate health and hygiene behaviours) | Aim: to improve school effectiveness measured in terms of equal opportunities for schooling and equitable learning outcomes. It subsumes the three Schemes of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and Teacher Education (TE). Provides children with free textbooks and digital learning and teachers with training |

| Budget: Rs. 26,129 crore | Budget: Rs. 11,500 crore | Budget: Rs. 620 billion | Budget: Rs. 27,957 crore |

A large part of government aid towards schools is directed towards sanitation and mid-day meals, with special schemes for the same. The important factors, such as the provision of digital education and female teachers, have relatively smaller schemes with a smaller budget.

Conventionally, one would expect the drop-outs to be caused due to lack of sanitation facilities, or mid-day meals. This was the need till a few years ago, and to some extent, is still needed in some schools. However, our circumstances have changed, and so the focus of our resources needs to change too.

Previously, a majority of parents looked at municipal schools as mere caregiving centers with such facilities, where they would send their children to eat and play when they would go out for work. However, our research suggests that now there is a major shift in parents’ perspectives of school.

While previously, schools were looked at as merely a center where parents could send their children while they worked, now they are looked at as education hubs. Students, as well as parents are gradually understanding the importance and seriousness of education that, in today’s age, is a necessity to break out of the cycle of poverty for weaker socio-economic sections.

Now, field conversations with a few parents suggest that in some cases, the students are pulled out of school as they do not learn much and only go to play, which is a waste of money. To reduce these drop-outs, the government must adapt to this shift in perspective, from emphasis on school facilities, to a progressive education.

Students are no longer looking at school facilities, but those school factors that enable and provide opportunities for employability. This education includes digital learning through laptops, tablets, and desktops and encourages students to study in schools with English as the medium of instruction.

Furthermore, the need for free textbooks has risen. Students are becoming serious about their studies, and these textbooks provide them with the means to achieve their academic goals without having to worry about the burden of the cost of education. Female teachers serve as an additional factor that help prevent dropouts, especially for girls, due to the school environment they create that makes students feel comfortable to learn and grow.

Now, the proposed government schemes should be directed towards a primarily progressive education. In order to reduce drop-outs effectively, it is essential to direct resources towards the quality education of these students.

Here are a few takeaways:

By reducing drop-out rates effectively, the impact is an improved employment rate due to a quality education where municipal schools are looked at as education hubs rather than mere caregiving facilities. This breaks the cycle of poverty for first generation learners and leads to equality in education. These students represent the youth of our nation. Effective steps taken to reduce such drop-outs will reap the benefits of India’s human potential - leading to greater growth and development.

1.7 Before and after of Dharavi as a hub of education

The idiom of ‘educational outcomes’, in contrast to the ‘learning outcomes’ provides a broader and better understanding of the overall status of child (Fatuma, Arnot &Wainaina 2010); learning outcomes usually typify measurement of specific skills or subject based knowledge whereas educational outcomes enable us the scope to capture the cognitive processes emerging from the non-formal settings in addition to the formal ones. They represent a more cumulative estimate.

PART 2 – QUESTIONNAIRES, SURVEYS, AND INTERVIEWS

As part of my research, Ipersonally interviewed 69 parents and 20 teachers from 11 primary schools in Dharavi during July and August 2021. I prepared a questionnaire and did a survey via Google Formsof parents and primary school teachers to understand the various issues around slum children’s primary education.

Given below are the two surveys that were sent out to parents, teachers, and principals of schools in Dharavi.

Image of questionnaire for parents:

Image of questionnaire for principals and teachers:

2.1 POSITIVES FROM THE SURVEY

2.2 NEGATIVES FROM THE SURVEY

2.3 COVID-19 IMPACT ON PRIMARY EDUCATION

Dharavi is a community spread over 2.5 sq. km., and represents life in Mumbai’s slums. With a population of 8-10 lakhs, an average of 8 people stacked up in 10X15 rooms, without a proper kitchen and toilet facilities, the level of chaos was extremely high when the pandemic hit the community. There were worries, and rightfully so, that Dharavi would potentially be the hotspot of COVID-19 due to the infrastructure, functioning, and way of life.

With regards to education in the slums, surveys with parents and teachers revealed the following:

However, the people of Dharavi, and MCGM, stood together in this fight and emerged victorious not only once in 2020, but also during the second wave of 2021. Dharavikarsgot tough as the virus dawned and came out as a shining example 9 months later. In fact, Dharavi’s death rate was 0.47%, much lower than Mumbai’s 1.5% and India’s 1.4%, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

PART 3 – CONCLUSIONS AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

There is no doubt that poverty, or low incomes, adversely affect the quality of education at the macro, country level (UN MilleniumProject, 2005), the meso, region and school levels (Govinda, 2002; Michaelowa, 2001; Watkins, 2000) and the micro, household level (Harper et al. 2003; Watkins, 2000). In most places, the poverty and education nexus is complex, partly attributable to the difficulty in distinguishing the effects of one on the other. Dyer and Rose, 2006, reported that education deprivation is not caused merely by poverty but also by related factors, as we can see in the case of Dharavi’s primary schools. These factors are closely related to gender, caste, labour market opportunities, and the quality of learning and facilities in the school.

The financial burden of education is the largest and most prominent issue. Socio-economic status of the household (Basu& Van 1998) and parent’s income (Ilahi, Nadeem et al., 2003), especially the mother’s (Ray 2000, Basu1992) affects the prevalence of the working conditions of the child. According to the UNICEF survey of urban areas in seven Indian states, monthly household expenditure on primary education per child as a proportion of per capita monthly consumption expenditure is remarkably high, ranging between 11 to 21 percent (Mehrotra, 2006). For slum-dwellers whose primary occupations include daily-wage earners, just the cost of one textbook causes a big dent in their savings. Children are often employed as helpers in household enterprises such as shops, grocery stores, tea stalls, tailoring shops, salons and slaughter houses etc. Other than these, children indulge in domestic labour or as helpers in the self-employment activity the household chooses for subsistence and a certain standard of living.

Interestingly, low-income families now are willing to make sacrifices to ensure their children get a good primary education.Governments can adopt schemes providing free textbooks, uniforms, and mid-day meals such as the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan and the Mid-day Meal Scheme.

As schools in Dharavi are now doing, teachers can go personally to visit students’ homes to help understand the financial situation and adopt a flexible fee payment schedule. Monthly door-to-door home-based counselling serves extremely helpful.This puts families at ease while also allowing children to remain optimistic about their future. Parents, some of who work multiple jobs to make ends meet, have also agreed that having a school with low-cost fees takes off a huge burden and in-fact serves as a fruitful investment which they did not have the opportunity for.

Labour market opportunities also serve as a major barrier to education. Conversations with parents and teachers from the survey highlighted that families shift to villages regularly when there are job opportunities. This causes irregularities in learning. Also, when parents are off at work, a lot of time students tend to ‘bunk’ school while their parents are under the impression that they are being educated. However, they all have enrolled in schools. This evinces that the enrolment ratio in school determining the performance of the school or the child is not truly reflective. Labour also gives an experiential account that shapes the child’s mind in a certain way; these experiences are to be understood as a cumulative factor, thereby bringing in the factor of past work as an important characteristic of child’s growth. The psyche of the child is affected by factors such as the power dynamics in the family (patriarchy, control & discipline), exposure to impolite behaviour, abuse or corporal punishments, partiality & insensitivity etc. Schools can implement vocational training activities such as sewing (clothing is a major wage-making industry) for students. This not only serves as an enjoyable activity which can be introduced as a game, but can also prepare the students for the labour market in the future.

School facilities and quality of learning impact parent’s decisions of whether or not they should send their child to school. While some parents look for quality education via good teachers and resources, others look at the facilities. Good teachers serve as role models for students helping them imbibe certain values such as respect, kindness, and hard-work. Surveys told us how parents are now looking at schools with closer proximity to homes due to safety concerns and lesser traveling cost. Facilities such as computer and science labs, for higher degree learning which serves useful in the future attract a large number of students. Even mid-day meals provided in schools serve as a huge attractive factor for parents. Libraries and classrooms with appropriate furniture (desks and chairs) allow students to explore and read in their own time keeping students motivated. Some schools even have regular medical check-ups for their students to ensure they are healthy, taking away this expense at the hands of parents. Playgrounds allow for effective socialization among students which form an effective component of the education process helping in networking in the future.

Furthermore, languages taught in school make a difference when it comes to the impact of education. Schools which have English or Hindi as a medium of instruction see a higher enrolment of students as these languages can help students become confident and also move out of the state in search of job opportunities. Having such language skills can greatly emphasize and scale up the magnitude of the impact that education has on Dharavi children. Governments must invest in such facilities to see primary education bringing around an impact in such Dharavi slum students’ lives.

To summarize, the following are 20 key specific recommendations that policy makers must consider to help improve primary education in key urban slums like Dharavi, which in turn can help improve the slumdwellers’ future quality of life and income-generating ability:

All of the above are easily implementable solutions that will not make a big dent on the government’s finances. The above solutions can dramatically transform primary education – which can be the lifeline for the transformation of urban slums in India.

REFERENCES

Alexander R (2001) Culture and Pedagogy: International Comparisons in Primary Education. Oxford: Blackwell.

Arputham, Jockin and Sheela Patel (2007), “An offer of partnership or a promise of conflict in Dharavi, Mumbai?”, Environment and Urbanization Vol 19, No 2, October, pages 501–508.

Arputham, Jockin and Sheela Patel (2008), “Plans for Dharavi: negotiating a reconciliation between a state-driven market redevelopment and residents’ aspirations”, Environment and Urbanization Vol 20, No 1, April, pages 243–254.

Biggeri, Mario, Santosh Mehrotra and Ratna, M. Sudarshan 2009. ‘Child Labour in Industrial Outworker Households in India’. Economic and Political Weekly 44(12): 47-56.

Empowerment of Future Generations in Urban Slum Pockets through Health, Education and Skills Programmes - United Nations Partnerships for SDGs platform. (2021). United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=30834

Government of India 2009. Right to Education Act.

Govinda, Rangachar, Status of Primary Education of the Urban Poor in India - An Analytical Review No. 105, Research Report, UNESCO, 1995.

Gupta I. and Mitra A. 2002. “Rural Migrants and Labour Segmentation: Micro-Level Evidence from Delhi Slums”, Economic and Political Weekly, 37

Heady, Christopher 2003. ‘The Effect of Child Labor on Learning Achievement’. World Development 31(2): 385-398.

Juneja, Nalini, Primary Education for All in the City of Mumbai, India: The Challenge Set by Local Actors, NIEPA, New Delhi, 2000.

Mathur, Om Prakash. “Slum-Free Cities, national urban poverty reduction strategy, 2010-2020.”

Ministry of Housing & Urban Poverty, Alleviation, Scheme & Programmes for the Poor. 2012.

Morais AM and Neves IP (2011) Educational texts and contexts that work: Discussing the optimization of a model of pedagogic practice. In: Frandji D and Vitale P (eds) Knowledge, Pedagogy and Society: International Perspectives on Basil Bernstein’s Sociology of Education. London: Routledge, pp.191–207.

Nikel J and Lowe J (2010) Talking of fabric: A multi-dimensional model of quality in education. Compare 40(5): 589–605.

Rosati, Furio and Rossi Mariacristina 2001. Children’s Working Hours, School Enrolment and Human Capital Accumulation: Evidence from Pakistan and Nicaragua. New York: UCW.

Seetharamu, A.S., Indian Mega Cities And Primary Education of the Poor: The Case of Bangalore City, Paper presented at NIEPA at the Workshop on "Indian Mega Cities and Primary Education of the Poor", September, 1998.

Siraj-Blatchford I, Siraj-Blatchford J, Taggart B, et al. (2007) Qualitative case studies: How low SES fami- lies support children’s learning in the home. In: Effective Pre-school and Primary Education 3–11, Promoting Equality in the Early Years. Report to The Equalities Review. London: DfES.

Sirohi, Rahul Abhijit. 2008. Gender Discrimination in India. Department of economics, Ca’foscari University of Venice. Online published thesis.

Sriprakash A (2010) Child-centred education and the promise of democratic learning: Pedagogic messages in rural Indian primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development 30(3): 297–304.

Surabhi Patel, 'Education of Children From Urban Slums' (New Delhi: Department of Education, ?National Council of Educational Research And Training) p. 16. (Mimeographed).

Tilak, J.B G., How Free is “Free” Primary Education in India? Economic and Political weekly, PP 275-282 February 3, 1996. Pp 355-366, February 10, 1996.

Tribune News Service. (2019, September 21). Empowering slum kids through education. Tribuneindia News Service. https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/archive/j-k/empowering-slum-kids-through-education-835652

Udipi, S.A., M. A. Verghese, and M. Kamath. 2011. “Attacking urban poverty: the role of the SNDT women’s university, Mumbai, India.” International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 1(8).